Hey guys, it's Scott.

It's Thursday, May 26. I just wanted to do a post about a topic that's been on my mind for a while, and then sort of address a couple other things at the end of the post. But one thing that I was always told as a creator coming in was that you have to be one of three things to succeed in this business—you have to be good at what you do (you have to be like a good writer, a good artist), you have to be fast (so you can't miss deadlines, all that stuff), or you have to be kind. And if you have two of those three things, you can succeed. But without two of those, you're sort of dead in the water, right? You can be good, but if you're not nice and you miss deadlines, you're out. If you're a kind person, but you're not particularly talented and you miss deadlines, you don't have a chance. But if you have to, the third one can be sacrificed in some way. Although I very much disagree that if you're a kind person, if that one is sacrificed, for the most part it catches up to you. If you're an asshole, you wind up without work because people don't want to work with you, editors don't. So I have to say that one in particular is not one that you can really sacrifice.

But the point I want to make is that I think there's a fourth category that nobody talks about, because some people think it's crass, some people think it's not artistic. Well, not even that it’s not artistic, but it's a difficult thing to discuss, and for me that fourth thing that's really crucial, I call it triangulation, like an ability to triangulate. And it's a business mind, it's a math mind. And it's a way of getting across what you want, the story that you care about, while understanding the context that you're functioning in. And it transcends all kinds of levels of the business. It transcends creative levels, it transcends political levels within the company you’re working for, it transcends in the way that it allows you to move through these different categories and neighborhoods of comics well, if you can do it, and fan relations, all of it.

So for me, what it is—I'll give you examples, but it's the ability to understand how the story that you're trying to get across will be perceived, internally and externally, and adjusting your bearings to be able to get it through the way you want by addressing that context. This is by doing whatever things you can possibly do on the page, off the page, to ease that in. So that also means understanding the politics of a company entirely. So being nice is very different than being savvy. When I was at DC, I was nice. I was an asshole sometimes, don't get me wrong, like I I've said it many, many times, but I would fight with my bosses and all of that stuff. I think part of me was looking to get fired because of the pressure early on, but I was generally nice. But being nice is different than understanding the politics and the kind of machinations of the company and how you can convince people to do things there because it's in their interests when they don't see it that way.

So I'll give you an example. So from the earliest days—Black Mirror. Black Mirror was a story that shouldn't have happened. I used two artists on that book that weren't conventional Batman artists at that time, and Grant Morrison was doing something very, very different from what I wanted to do. But my gamble with that was that this was a story that I really cared about. I wanted to go big with it. I had this belief in this theory about Gotham being the greatest antagonist in literature and that it would adjust itself to Dick Grayson and change and all of this stuff. And I wanted to do it through James Jr and all of these things that were risks. So I had to convince Mike Marts that what would really work and get it attention was to counter-program what Grant was doing. And I wanted to do what I wanted to do anyway. I wanted to work with Jock and I wanted to work with Francesco, all of it. So the story didn't change, but what changed was the way that DC viewed it. I said, “listen, Grant is doing this incredible epic, my favorite Batman run of all time, that is maximalist, that's just a reexamination and an inclusion of Batman's entire history into one joyous, cerebral, visceral bomb of Batman stuff. A firework. For me, let me go dark and grounded and give an alternative path for people who might feel as though that story is too big for them in a certain way.”

Again, it's my favorite run in history, but I understand that sometimes it can be intimidating because it's so ambitious. So I did the story I wanted to do, but the way I got it through was to get them to understand that it would create a space that could be commercial for fans that maybe wanted something more Gotham-centric, more grounded, more gritty, more urban, all of that stuff. But at the same time, the story was pretty ambitious its own right. It introduced a character that definitely got people upset for a moment, even though I don't know if people now think back on it that way. People were angry at me, as a brand new writer, for introducing James Gordon Jr, who was Jim's son and was a possible (and eventually confirmed) psychopath. It made them feel Jim wasn't a good father, all of this stuff. How dare I, I'm brand new, how can I change things, etc. But that got swallowed up in the discussion of the story because of the great art that was in the book, because of the backup feeding the feature, all of the kinds of fun things that we were trying to do as a team overwhelmed that conversation. And all of that is deliberate math, is what I'm saying.

Another example—Dark Nights: Metal. Nobody wanted us to do Metal, they wanted to bank on the Geoff Johns story Doomsday Clock in that way as a fulcrum for things. And I was fine with that. I didn't care if Metal affected things in a huge way. I wanted it to be able to create a space for us to land and do a new Justice League. I never cared if my stuff affected the whole DC Universe, I just wanted it to be able to create a lane for the kinds of stories we wanted to tell. But at that time there was this big clash internally, not to spill too much tea, about would it be Doomsday Clock or Metal and what would connect, and I just said that I don't really care what connects, what I want to do is something that brings back the joy and the fun of superhero events at a moment when there was tremendous fatigue about events, because it was 2016 and I think people were jaded about the political landscape and contention. And I thought there was an opening to do something that was just fun and zany, but secretly was very personal to me about the darkest moments in depression, the way that you feel when you're absolutely a your rope’s end and all you see are horrible versions of yourself and the way in which super heroes, especially Batman, had gotten me through those things. So it meant something to me, but I was pitching it to them as fun.

And the other thing, the way that I got it through, even though there was a question of should we even do it at that time or just focus on on other events like Doomsday Clock, was to say to them, “look, it gets you assets. Here's the assets—all these evil Batman, it gets you Batman Who Laughs. Let us do this. Look at Greg's designs.” And it creates the Dark Multiverse, one of the things I'm proudest of at that time. It creates not just a set multiverse, but an ocean on which that multiverse floats that you can pull anything from. So I had to go in and pitch to them that this is what it means to me. I didn't care if they really knew what it meant to me, but I cared that they understood that, Trojan horse or not, it would get them what they wanted and there was no reason not to do it, because it could function in its own lane. And then ultimately what happened was Doomsday Clock, just schedule wise, couldn't really connect to the rest of the line, and so they wound up hitching a lot of things to Metal. And then when we did Death Metal, we tied it back to Doomsday Clock and brought a lot of that stuff back in in conjunction with Geoff. But ultimately, the point is that the way that I was able to get Metal through and be exactly what we wanted was to think of it in terms of what they needed. See the problem they were facing and be like, “there's no way that these things conflict with each other. Instead, they complement each other and get you more and more stuff.”

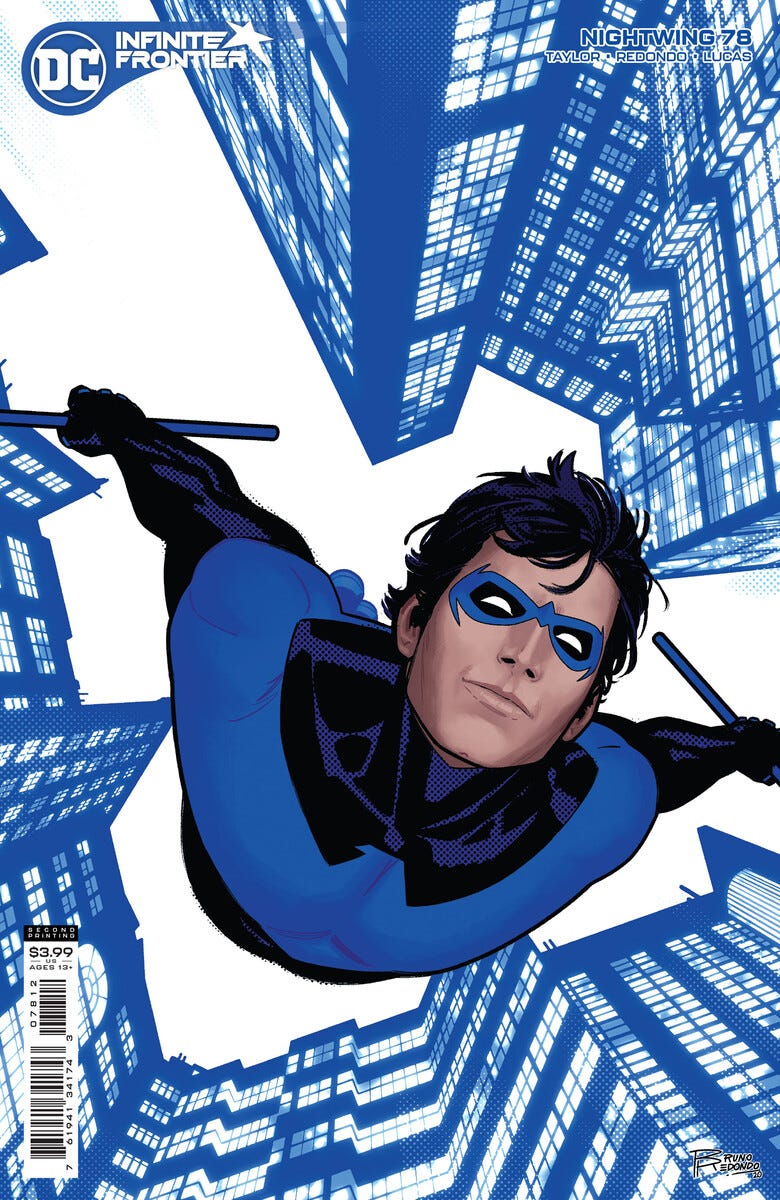

Now you can see creators up and down the line that are really good triangulators. Tom Taylor, to me, is one of the best in a really great way. Look at Nightwing. He sees exactly what was happening with Nightwing when he took the job. The book had been in disrepair for a long time. That's no offense to the creators that were on the book, they had tried a lot of things that I thought were really cool, but some things hadn't worked. And a lot of things had been blocked, like there were editorial mandates about not bringing him in Barbara together to all kinds of things that really just didn't make a lot of sense, in my opinion, with Nightwing. And that's why I wanted to do this Nightwing story that has a lot of similarities to what Tom is doing, but had a different big surprise in it, which maybe I'll still do someday, but that's triangulation, right? There's no need for it right now.

But Tom clearly is coming in and saying “this is a reparative run, here are the things that we're missing from Nightwing, the spirit of Nightwing. I'm going to give you fan service, I'm going to give you nostalgia, I'm gonna give you all this…” and all of that is hiding, or if not hiding then is the wrapping around the big slow burn massive epic story he's telling with Heartless, which is going to be amazing. So it's a great math he's bringing to that book and it's a self aware math about saying to fans, “I know what you've been missing. I've been missing it too, here it is.” And he's building towards what he wants. That's a great triangulation. Other creators, sometimes they're not good triangulators and you see it, and they can absolutely overcome that. It's not a crucial thing. You can just keep doing stories that take a character that doesn't need the thing you're doing to them, or you're doing something that's tone deaf to them at that time, and honestly by power of the story’s quality, you can surmount those challenges. So it's not crucial, but it's really helpful.

To me, it's like a muscle or a part of your brain that if you can activate as a creator, you'll have a much, much, much easier time. I know it sounds corny, but it's a fun thing to think about sometimes. Okay, I want to get this story through, what do fans think? Like when I wanted to do Gordon as Batman, right? I knew that was going to be really contentious. Or when I wanted to do Zero Year, I wanted to do Batman's origin. Another example. I knew it was going to be contentious. A lot of the things we did on Batman weren't things people wanted—giving him a possible brother, creating an organization that he didn't know about. There were things that people reacted poorly to, and I got a lot of negative messages privately that I never showed. I just didn't show them because I didn't want you to see them.

Sidenote to creators, if someone is tweeting terrible things at you, nobody fucking sees it unless you tweet it. If you don't respond, or you don't highlight it, nobody knows it's even being said half the time. So just ignore it, or address it in whatever way you want. Do what you want. But I'm just saying there's a misconception that everyone's seeing what's being said to you. Nobody's seeing what's being said to you except you. Other times, yes, if it's a real issue that's popped up in the conversation, address it. I'm just saying if some troll is coming at you saying “you’re ruining blah blah blah,” like, why give them the oxygen?

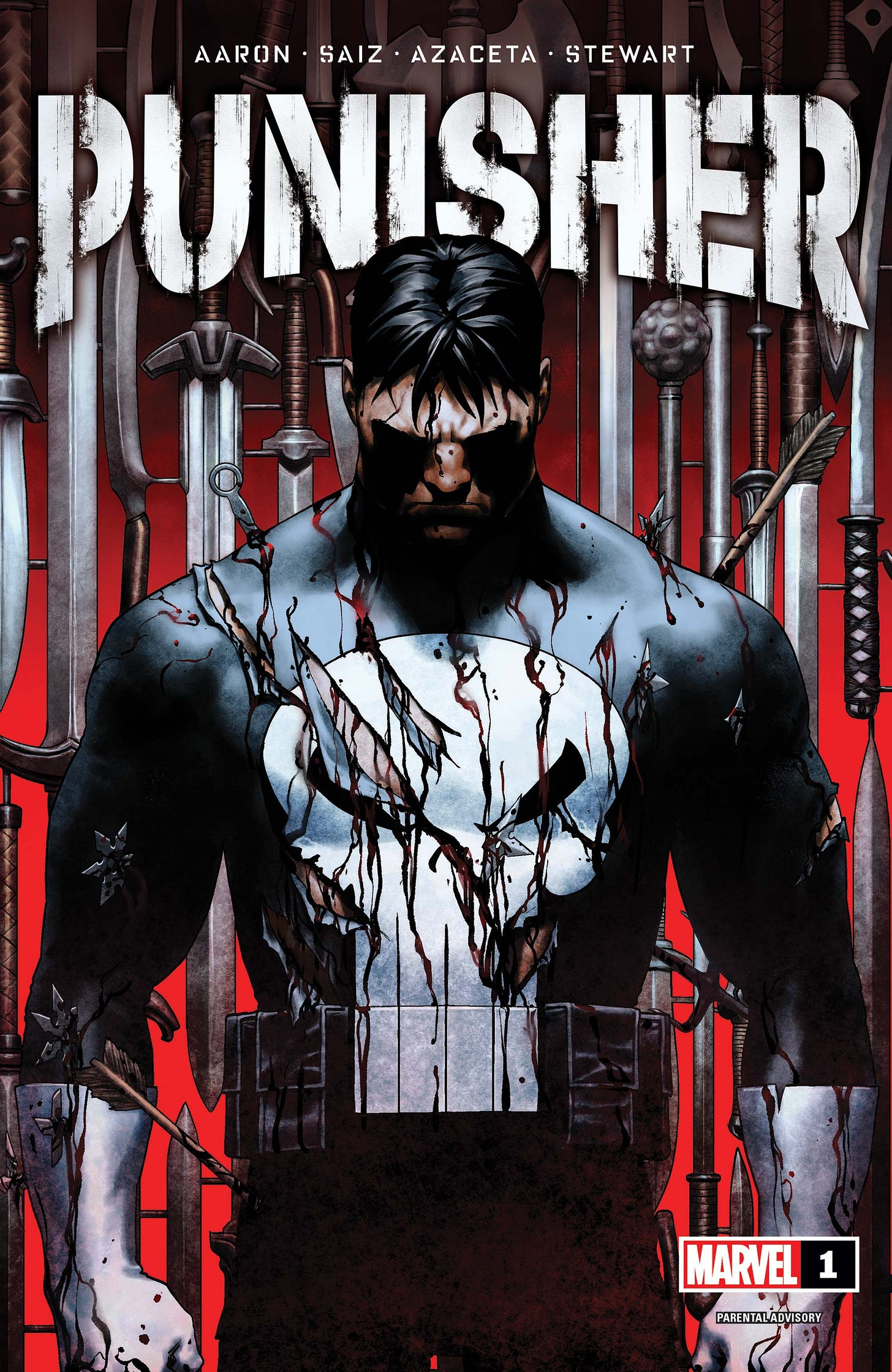

But back to the point. Yes, some creators, they'll go back, they'll introduce elements into a character's life that are really upsetting—take away a love interest, change something from their origin. You see it happening right now, for example, with some books like Punisher, which I really like and I like what’s happening there. I love ambitious, daring things that want to change, or maybe it's a trick, but at least play with changing what was there in some way to get you to rethink the character’s mission. But the point is, you don't have to calculate. You can just go headstrong, right into it.

And especially as you get bigger, like, I'm in a position now, luckily, where I don't have to give much thought to triangulation, like if I came in and did something at Marvel or whatever, but I would. I promise you, I would. I'd want to think, what a fans want? Does that change what I'm going to do? 100% no. But do I want to address what fans want in some way, like I did when Gordon was Batman and he looks at the audience and he says, “this is the dumbest idea in history, I know it now give me my damn Batmobile.” Or at the beginning of Zero Year, the fact that I did it as a post apocalyptic story with a sleeveless Batman with a crossbow and an overgrown Gotham as the opening image to short circuit expectations that it was just a retread of an origin. That's triangulation, you understand?

So it goes from creative decisions all the way down. Like it's understanding how to get through what you want, internally at a company, how to posit it in such a way or position in such a way that fans give it the best chance possible, that it has the best impact and reaches the most people, because that's what we're trying to do as writers, all of it. So anyway, that's something I would just bring up as a topic we can return to, but it's very important thing. And if you can do it, I think it's a huge element in terms of comic book industry success.

Okay, so I said last time, I'm going to address questions here and there from fans. I know this one went long. So I have a quick one here that I think is good. Tyler just sent it over.

danielgonz asks

How do you adapt true stories into fiction? As in, how do you structure something that’s happened to you or how do you create an arc to someone’s life?

That's really hard. I mean, the way that I would address that is I think that you have to stay true to what the story is about. A similar question, I think, is like, how do you deal with true events in fiction? Full disclosure, I'm dealing with that right now in a story that I'm doing where there was an element of violence that the events of this week really got me thinking about, like, do I want to have guns? Do I want to have these things in a story? But the truth is that the story is about those things, not gun violence, but it's about hyper-violence and all of this stuff. And so there's a reason to keep some of it in. I think that it's important, if you justify the use of what you're doing and it's about real world events in a way that's thoughtful and substantive, to not shy away from using things in the real world. If you're using them in a tone deaf way or sensationally, 100%, you don't want the conversation to become that thing unless you're prepared to deal with it.

And I'm not talking about a story where you have horrific gun violence and it's about gun violence, nothing like that. It's sensitive to the degree that I was sensitive when I was doing Joker, and there was the shooting in the movie theater where somebody claimed to be inspired by the Joker. It was very much like, “look, I can get across the violence of the Joker in Death of the Family without having him use guns. He can go around and he can break necks and he can do this and it's scarier because it's more intimate.” If it really compromised something, I would have stuck up for it. But that's a decision creatively that gets what I want out of it and isn't just genuinely insensitive in a way that doesn't make sense. So there’s that.

In terms of bringing people's lives and real stories to the page, I think it's about creating the best narrative. I know what you're saying, like, you're saying, “how do you structure something that's unstructured into a narrative that has three-act structure?” All of it. But you have to focus on what it's about, right? Look at biographies, like, look at the movie King Richard, look at A Beautiful Mind. It's a narrative that’s showing your character getting over some internal conflict in some way. So are you going to have room for everything about that person? No. But you're trying to make kind of a single point about the thing that inspires you about them the most and whatever else you have room for, but that thing is your compass to be able to create a narrative structure out of an emotional arc, a plot arc, etc. So you focus on on that one thing and use it as the protractor to start building that arc, okay?

All right, guys, thank you so much. Again, it's been a horrible week. I try to use this space as a place you can come to think about craft and tell stories that are important to you. I'm a big believer in sensible gun reform and also in providing services to address mental illness. Both. I don't see why this has to be a binary discussion. I do absolutely think that gun law regulation is too loose. I believe in gun ownership, I don't believe in anyone being able to get a gun regardless of background history or any of it. I also don't believe in providing no safety net for people that are struggling with mental illness at all the way we are. I just think it's it's ridiculous that we can't find some way of bringing these two topics together as opposed to being opposing polls that we gather around. Anyway, I hope you have a decent week. You stay safe, all of it. Lots of love, and we'll talk next week.

S

Share this post